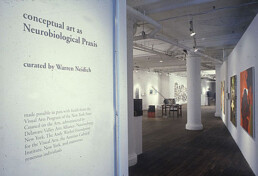

Conceptual Art as Neurobiological Praxis (1999)

Thread Waxing Space, New York City, NY (US)

Curated by Warren Neidich

March 25 – May 1, 1999

Participating artists include Rickie Albende, Uta Barth, Sam Durant, Éric Duyckaerts, Spencer Finch, Carl Fudge, Rainer Ganahl, Liam Gillick, Douglas Gordon, Grennan & Sperandio, Jonathan Horowitz, Kim Beom, Anne Kugler, Ann Lislegaard, T. Kelly Mason, Jack Pierson, Jason Rhoades, Matthew Ritchie, Andrea Robbins, Thomas Ruff, and Charline von Heyl.

The history of conceptual art, like all art historical movements, is continually under a state of siege as the changing cultural milieu in which it lives—the facts of its origins, development, and relevance—mutates. Conceptual art, like situationism which preceded it, and minimalism, pop art, and op art which was contemporaneous with it, had its own founding artists who, in their desire to create an identifiable character (or brand) unconsciously tried to define and limit the parameters of its meaning, economy, and distribution. This, of course, is always hopeless: at best creating a discourse, at worst creating a dogmatic regime that becomes deterministic and exclusive, and in the end results in its own demise.

Such is the history of conceptual art, which in its “pure” form, according to Lucy Lippard, lasted only seven years: from 1966–1972.1 However, conceptual art is not and was not, in spite of itself, a linear practice and emerges in the context of many streams of art practice including lettrism and situationism, philosophy including structuralism and phenomenology, infomatics like cybernetics, psychosocial discourses like psychoanalysis and Marxism, and the political activism of the late 1960s. The degree to which each of these contributes to the active image of conceptualism is the result of different networks of relationships that form between them at different moments and create nodal intensities in an open—not closed—autopoietic system of multiple feedforward, feedback, and reentrant systems and temporal synchronicities, which are formed as systems of porous information modules linked together by dynamic, intermittent, temporal synchronicities.

I am not here trying to analyze this system of relations into some finite set of determinations, but instead to give the reader some idea of the massive complexity of this system and the degree to which organizations of art breathe and live in a system of multiple meanings, realities, and definitions which in the end give them very complicated and folded structures that almost defy interpretation and analysis. For it is within this complexity that other forms and other meanings hibernate, laying latent, remaining in a state of hypothermia and very slow metabolism, awaiting the proper set of conditions in which to emerge and once again become. We see examples of this all the time as certain artist’s work all of a sudden becomes once again important, or in the way certain bodies of works that had gained notoriety in their day begin to be appreciated and recuperated.

This is certainly true of the many careers of Marcel Duchamp, but recently we have also witnessed this phenomenon in a renewed interest in the work of Robert Smithson, Anthony McCall, and Gordon Matta Clark. Some would argue that an explanation of this can be found in the way that the social, political, historical, psychological, and economic conditions of the late 1990a and the early twenty-first century share important qualities with those that defined the late 60s and early 70s, such that this recovered work expresses key insights common to both eras. For instance, the work of Sol LeWitt (very much influenced by infomatics of the 60s) develops renewed intensity in the context of new media art today. His now famous quote from “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” published in Artforum in 1967, “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art,”2 sounds very much like a quote from Cybernetics by Norbert Wiener.3

Others would argue that, in fact, these works—and other works that carry, for instance, a minimalist codon—were never understood completely and their reappraisal concerns a kind of historicity in which the works that followed have given their primary sources new meanings not originally appreciated at that time, but which emerge within the newly configured cultural context. For instance, ideas of time and space have been radically altered since the invention of the internet. With this new understanding, primary works of art that forewarned of this new condition—for instance Robert Smithson’s Quasi-Infinities and the Waning of Space (1966) and John Baldessari’s Painting for Kubler (1969)—have added significance. Time and space are now generally understood as intensive, folded, and complex, and these mutated conditions lend new levels of understanding to what these artists were intuitively trying to say.

Another permutation of this explanation concerns the way a work of art or a movement is never really understood at all and that other meanings emerge that lay sleeping in the interstices of their being. That is to say, the emerging contexts reconfigure the artworks themselves so that their determining factors are not what they were understood to be. In fact, the founding artists of such movements were responding to conditions that had not yet formed, and these artists—as they are simply observers, spectators—are a product of newly formed, culturally derived subjectivities and stumbled through their creations without understanding what they were doing, but doing so with extreme elegance.

Finally, another possibility for the emerging interest in art of the past is the condition of the observer who interfaces with it. Such is the condition of the mutated observer whose reconfigured neural networks, reset as they have been by mutating temporal and spatial conditions resulting from the cultural incorporation of new media practice at the end of the twentieth century, view and experience the work in quite new and radical ways. This discussion is especially relevant for conceptual art and recently a number of exhibitions have attempted to throw new light on this history. Most notable are L’Art Conceptual, une perspective (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1990), Reconsidering the Object of Art (MOCA, Los Angeles, 1998), and Global Conceptualism: Points of Origins (Queens Museum, New York, 1999). Conceptual Art as Neurobiologic Praxis is another recent example of this historical reappraisal by also attempting a rereading, or expansion, of the root causes and concerns of conceptualism while at the same time linking it to the history of artistic and technological apparatuses and processes as they float between the investigation of perception and cognition on the one hand and artistic production on the other.

Jonathan Crary would link the parallel history of technologies of observation in the nineteenth century to the emergence of a new kind of observer.4 The same could be said, of course, about the late twentieth century. New media, according to the likes of Manuel DeLanda, moves us away from an extensive culture to an intensive one.5 Sequential, linear, hierarchical forms of information are substituted for by folded, nonlinear multiplicities of meaning. This new, intensive culture is expressed in an intensive subjectivity. One only has to glance at Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao or the graphics used in Wired Magazine to know how this subjectivity is expressed. This is another important subtext of Conceptual Art as Neurobiologic Praxis.